Métis Scrip

Author: Camie Augustus

Throughout the late 19th century, settling the west was paramount for the newly confederated Canada. Western settlement was part of Macdonald’s larger plan for building the country through his National Policy scheme, and clearing the title of the region’s Indigenous peoples was integral to this process. As a means of extinguishing the Aboriginal title of the Métis, the scrip policy was implemented in the North-West, part of which is now Saskatchewan.1

Scrip was designed to extinguish Métis Aboriginal title, much as treaties did for First Nations. However, the Métis were dealt with on an individual basis, as opposed to the collective extinguishment of title pursued through the treaty process. Much like the numbered treaties, though, scrip commissioners travelled to Métis communities and held sittings at various locations where Métis gathered to fill out applications for their entitlement.

Métis sitting around table during North-West 'Half-Breed' Commission, Devil's Lake, 1900 (image details) |

Scrip was implemented over several decades in three phases: in Manitoba in the 1870s; in the North-West in the 1880s; and in conjunction with treaties 8 and 10 in the northern part of the province. The policy continued to be the only means of extinguishing Métis Aboriginal title in Canada well into the 1920s.

Indigenous people gathered outside tent at the time of the "Half-Breed" Commissioner's visit, Snake Plains, 1900 (image details) |

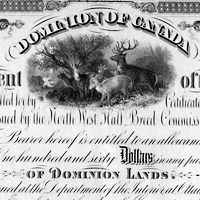

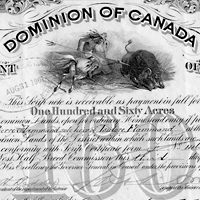

The basic premise to scrip was to extinguish the Aboriginal title of the Métis by awarding a certificate redeemable for land or money – the choice was the applicant’s – of either 160 or 240 acres or dollars, depending on their age and status.

Claimants had to fill out an application, sign an affidavit, and in most cases, received their scrip coupon on-site if they qualified. This process varied from commission to commission, but this format was standard to all phases.

Manitoba Scrip

Scrip was first used in Manitoba, where it provided a means to fulfilling the terms of the 1870 Manitoba Act – the outcome of negotiations between the Manitoba Métis and Ottawa following the 1870 Red River Resistance. The causes of the Resistance can largely be attributed to grievances concerning land title and political representation. The catalyst to the affair was the transfer of Rupert’s Land to Canada and the surveys which were conducted throughout the summer and fall of 1869 without the consultation of the Métis who inhabited the lands.

Concerned that their occupation of the land would not be recognized, the Métis petitioned Ottawa to consider their interests. Without a forthcoming or expedient response from the federal government, the Métis declared a provisional government, finally producing an incentive for the federal government to enter into negotiations.

In the spring of 1870, Alfred Scott, Bishop Taché, and Judge Black set off for Ottawa as the Western representatives, returning with the terms of what became the Manitoba Act.

The Manitoba Act laid out the foundations for extinguishing Métis Aboriginal title in Manitoba and established who was eligible to participate in the land grant. However, it did not identify a process for distributing the land. It was through a series of orders-in-council over the next few years that the issuance of scrip was employed as the means of distributing 1.4 million acres of land to the Métis inhabitants of the original ‘postage-stamp’ province.

Scrip in Manitoba was slow to be implemented. Although the agreement had been ratified in 1870, the distribution of scrip did not begin until 1876. The Commissions were plagued with administrative problems, creating frustration for many Métis. Many families left Manitoba for the west, some settling in what is now Saskatchewan, while others moved on to Alberta and south to Montana. Saskatoon entrepreneur and business man James Clinkskill discusses this migration.

Discussion of the Paper on "Shopping in the Early '80s" Given by Mr. J. Clinkskill Before the Saskatoon Historical Society (image details) |

Claims still outstanding from Manitoba forced the government to implement a supplementary commission which ran simultaneously with, although independently of, the North-West Half-Breed Commission. For this reason, the two are difficult to separate and have often been confused. To further complicate the issue, some of the North-West Métis making claims in the 1880s were original inhabitants of Manitoba. While they were not making claims under the Manitoba Act, they were originally eligible to do so. This unfinished business carried over into 1885.

North-West Métis Scrip: 1885-1889

This, then, provided the basis for scrip in the North-West (now Saskatchewan and Alberta). Much like the circumstances in 1870, it is impossible to assess the scrip policy without an eye to the tensions between Ottawa’s intent to settle the west and pre-existing Métis claims to the land. Circumstances leading to the 1885 Rebellion and the implementation of a scrip policy were again land-related issues: as the government moved in to survey lands, the Métis became increasingly concerned that their occupation and traditional title would not be recognized as legal ownership under the new system. Dominion Land Survey reports, written annually by the Surveyor General, provide more details.

Government records and correspondence clearly indicate that they were aware of these complaints; warnings from North-West officials and missionaries clarified this.

Individual Métis communities throughout the North-West launched a series of petitions to Ottawa outlining their concerns. Throughout the 1870s and early 1880s, these petitions continued, a clear sign that these outstanding issues needed to be settled.

Department of the Interior, Dominion Lands Branch, Correspondence Regarding Assorted Métis and Settler Petitions (image details) |

In addition, the numerous warnings sent from officials in the North-West Territories to Ottawa indicated that the Métis desired assistance in transitioning to a new way of life: the decline of the buffalo on the prairies was all but complete by the 1880s, and many Métis communities were experiencing the effects of a large-scale economic transition amidst a growing settler population and a declining fur trade. However, these warnings went unheeded by those in Ottawa. Eventually, officials responded,2 but the delay proved to be costly.

The personal testimony of Patrice Fleury, a Red River-born Métis who lived in Saskatchewan during the years leading up to the 1885 Rebellion discusses this period.

Patrice Fleury collection: File contains the reminiscences of Patrice Fleury who was born in Red River in 1842. He describes Métis Buffalo hunts and the debates in the community leading up to the Riel Rebellion of 1885. (image details) |

An order-in-council in January of 1885 marked the first definitive indication that the federal government intended to deal with these complaints which had persisted since at least 1879. The order authorized an enumeration of Métis inhabitants, but it did not actually authorize the use of scrip. It was not until March that commissioners were appointed and a specific course of action was laid out. By this time, though, the Métis had begun to gather and prepare for action under Louis Riel. As the scrip commission was getting underway, fighting broke out at Duck Lake.

Although the Commission commenced in the spring of 1885, the legislative authority itself was set out by the 1879 Dominion Lands Act. Section 125(e) of the Act authorized the Governor in Council

The Act was vague, though, and did not outline any formal policy or procedure for this process. Again, as with the Manitoba Scrip Commissions, this policy was laid out through a series of orders-in-council. Throughout the 1880s and into the 1890s, twelve such orders served to define and clarify the scrip policy. Over the next few years, the commissioners travelled throughout the Territories accepting applications from the Métis for scrip.

The process of applying for scrip was cumbersome and confusing. First, an application (Form "D") had to be filled in and submitted. In many cases, the commissioners were dealing with an illiterate population, thus, the process effectively amounted to an oral interview. Aside from the standard questions, such as name, address, genealogical information, and other means of identification, the applications also inquired about previous and current land holdings. For example, the applicants were asked if they had a homestead entry, what became of it, and the value and improvements of their current land. The extent of inquiries into land holdings during the application process suggests an emphasis on the land and its settlement, not with the rights of the Métis. This point is verified by what is missing on the application itself: consent to the extinguishment of Aboriginal title.

Next, the applicant was required to confirm their identity. Each claimant was required to provide, by affidavit or "two reliable and disinterested witnesses,"4 that he was a ‘half-breed’ and a resident of the North-West Territories previous to 15 July 1870. Once this had been proven to the satisfaction of the commissioners, they would then provide the claimant with a certificate (either Form "F" or "G") indicating that the claimant was entitled to the amount of scrip which was indicated on the form. The Department was to be supplied with a similar certificate (either Form "H" or "I") duplicating the certificate issued to the claimant and providing a record for the Department. The same process was required for children, with certificates to be provided to them (on Forms "K" or "L") and duplicates to the Department (on Forms "M" or "N"). Those who submitted claims on behalf of deceased relatives also had to go through this process.

More challenges followed the application process. Following an approval, the grantee would need to locate and enter the scrip – a process which necessitated a trip to a Dominion Lands office. Next was the wait to receive patent to the land, provided there were no conflicts with other settlers or reserves made for other purposes, such as railway or school grants. Formalities, paperwork, and lengthy waits between each phase characterized the process.

The policy displayed an ignorance of Métis ways of life. Distance, for example, represented a hindrance for many. Travel during the busy summer months would have required entire families to leave their work and their homes for several days, first to visit the commission then again to locate their land.

Economic circumstances sometimes prevented Métis from reaching the commissions and applying for scrip.5 The process of filling out unfamiliar forms in, many cases, an unfamiliar language proved formidable. The bureaucratic nature of the application process itself would have seemed foreign and confusing, deterring many.6

Department of Interior petitions and correspondence: "Various petitions and government correspondence related to Métis and settler issues with the government in the aftermath of the 1885 Resistance. Includes concerns over agricultural markets, scrip issuance, the Rebellion Claims Commission, and local government" (image details) |

Between 1889 and 1901, scrip commissions continued to operate throughout Saskatchewan. Four types of claims were dealt with during this period: outstanding claims from the 1885 commissions; outstanding claims from Manitoba; new claims arising from land recently ceded through Indian treaties; and new claims based on the 1900 amendment allowing Métis born between 1870 and 1885 to apply for scrip (in previous commissions, only those born prior to 1870 were allowed to apply).7 These commissions operated essentially under the same policies which had been established in Manitoba in the 1870s and in Saskatchewan in the 1880s.

Treaty Scrip: Treaties 8 and 10

This next phase of the scrip policy came with the negotiation of treaties in the northern part of the prairie provinces. An increase of activity in the region due to the gold rush, namely miners and prospectors, brought the potential for conflict. Officials at Ottawa recognized the need for a treaty: covering the northwest corner of Saskatchewan, Treaty 8 was carried it out in the summer of 1899; in 1906, Treaty 10 ceded most of the northern part of Saskatchewan.8

This third phase of the scrip policy was notably different than the first two. Métis claims to Aboriginal title in the northern part of Saskatchewan were considered at the same time as treaties were negotiated. Government officials recognized the importance of Métis to the treaty process, and were concerned that they would hinder treaty negotiations if their claims were not dealt with, too.9 This differed remarkably from previous Métis claims, which were considered only after Indian title had been ceded by treaty. The Dominion Lands Act was amended in 1899 to reflect this change in policy, allowing claims from Métis residents who were born after 1870.10

Another difference was the amount of scrip issued. Previously, children received 240 acres or $240 while adults received 160 acres or $160. During this treaty scrip phase, though, all recipients received 240 acres or $240, regardless of their status or age.11

These changes in policy – particularly the removal of the age restriction – created new claims in addition to those in the treaty area. Métis who had previously been ineligible because they were born after 1870 could now apply for scrip. Consequently, the government dispatched separate commissions to deal with these new claims. The two commissions – the Alberta/Athabasca and the Saskatchewan/Manitoba – while not technically part of the treaty scrip commissions, were operating under the same legislative authority.12

The process for applying for scrip, however, was still much the same. For Treaty 8, scrip commissioners accompanied treaty commissioners and awarded scrip coupons on-site, much as they had done throughout the 1880s. The Commission travelled only through northern Alberta in 1899, but held a sitting at Fond du Lac in 1901. Consequently, many individuals were missed. Over the next few years, additional applications were taken while distributing treaty annuities in the region. Unlike previous commissions, though, the applications were not assessed on-site: instead, they were taken back to Ottawa for the Minister of the Interior’s approval. It wasn’t until the following year that scrip coupons would be delivered by the Indian Inspector. In total, over 1200 scrip claims were granted under Treaty 8.13

The terms and process for Treaty 10 scrip were much the same. All successful applicants received scrip in the sum of either $240 or 240 acres, regardless of their date of birth. In 1906 and 1907, scrip commissions were held in conjunction with Treaty 10 commissions at Snake Plains, Lac la Ronge, Stanley Mission, Southend, Ile-a-la-Crosse, La Loche Mission, La Loche River, and Portage la Loche.14 A few more applications were gathered in 1908. Over these few years, over 700 scrip claims were granted.

Fraud and Speculation

Ultimately, the scrip policy met the same end everywhere: the Métis still found themselves without a land base at the close of the 19th century. The speculation in Métis scrip, the fraud that often accompanied it, and the government’s refusal to protect scrip lands from these illicit activities deemed this policy a failure for the Métis. This subject is still debated in the secondary literature, but ultimately, government officials were fully cognizant of the role speculators had in the scrip process, and in fact, accepted it.15

What happened in most cases is that Métis lost their scrip to speculators for a fraction of their value. Scrip buyers, sometimes operating for the same outfit, often pre-arranged a set price for scrip.16 Bartering for a better price, then, became impossible. Other factors also contributed to the sale of scrip below its market value. Information about scrip was unclear to applicants, and many Métis did not appreciate its value.17 The Métis were often pressured to sell due to reasons of poverty, not to mention the difficulties of locating land. Métis lifestyles were not always compatible with an agricultural life: seasonal work in a semi-migrant economy was not conducive to the sedentary life required by farming. In some cases, it was a prudent decision of economy: speculators offered immediate cash. Reasons varied from individual to individual, but the presence of speculators at scrip commissions almost guaranteed that the decision would be made in their favour.18 Even land surveyor William Pearce – a critic of the Métis cause in general and of the scrip policy in particular – noted that the scrip process was infected with the unscrupulous dealings of speculators whom, he believed, were in cahoots with commissioners.

Eventually, the role of speculators became cause for legislative change. A Department of Justice memorandum written in 1921 clearly implicated the process of fraud within speculation of Métis scrip. In 1921, an amendment was made to the Criminal Code limiting the time prosecutions could be made in regards to scrip. The Department noted that:

Clearly, speculation and fraud occurred, and it occurred to the detriment of the Métis. Now, years later, the government eliminated any option for recourse by placing a statute of limitations on the very same fraudulent activities that it essentially supported throughout the scrip policy.

Métis Aboriginal Title

From the scrip policy’s inception, the expressed intent in the statutes was to extinguish Aboriginal title. Both the Manitoba Act20 and the Dominion Lands Act21 state this. But while the government clearly recognized and acknowledged the existence of Métis Aboriginal title in an official capacity, there was hesitation on an informal level to validate this concept in the same way they did ‘Indian’ title.

Prior to 1899, the Department of Interior held that Métis title would not be dealt with until Indian title had first been extinguished, suggesting a perceived stratification of Aboriginal title. This concept of stratified Aboriginal title was not yet fully developed in the 1880s, and in fact, did not appear until 1887.22 A change in official attitude about the position of Métis Aboriginal title occurred during the treaty scrip phase. An order-in-council recognized that "while differing in degree, Indian and Half-Breed rights in an unceded territory must be co-existent."23 Henceforth, the Aboriginal title of both Indians and Métis would be dealt with simultaneously.24

Anthropologist Joe Sawchuk (et.al.) outlines the history of Métis Aboriginal title, its legal basis, attitudes towards it, and contemporary legal concepts. He points to several legal problems of working within the current framework of Aboriginal title as decided in the courts for Aboriginal (non-Métis) cases where the understanding of Aboriginal title does not necessarily fit the Métis circumstance.25 He states, though, that this is of little concern since "the Manitoba Act, and several successive Dominion Lands Acts have already acknowledged their rights to Indian title."26 However, this is not entirely clear from a legal standpoint. As historical geographer Frank Tough points out, extinguishment of Métis title "remains unresolved."27 This is evident, he says, by the fact that "there is nothing in the process … which indicates that individual Métis consented to extinguish Aboriginal title."28 Assuming that the courts consider the terms of the Manitoba Act and Dominion Lands Act as a recognition of Métis Aboriginal title, it would indeed be the case that there was no explicit consent to extinguish those rights.

Department of the Interior, Dominion Lands Branch, Correspondence Regarding Scrip for the Métis of Lesser Slave Lake (image details) |

Conclusion

Unlike the effect of Indian treaties in the North-West, the protection of Métis lands was not secured by the scrip policy. In most cases, the scrip policy did not consider Métis ways of life, did not guarantee their land rights, and did not facilitate any economic or lifestyle transition. Instead, Métis scrip lands could be sold to anyone, hence alienating any Aboriginal title which may have been vested in those lands. Despite the evident detriment to the Métis, speculation was allowed to continue. While this does not necessarily preclude a malicious intent by the federal government to consciously ‘cheat’ the Métis, it illustrates their apathy towards the welfare of the Métis, their long-term interests, and the recognition of their Aboriginal title. But the point of the policy was to settle land in the North-West with agriculturalists, not keep a land reserve for the Métis. Moreover, Ottawa was unwilling to incur the costs of another reserve-type policy.

The scrip policy spanned almost five decades and held numerous sittings. Aside from the three major commissions held in the 1870s in Manitoba, the 1880s in the North-West, and in conjunction with Treaties 8, 10, and 11, other commissions were set up to extinguish Métis Aboriginal title. In 1889, the Green Lake Commission offered scrip alongside the commission of the Treaty 6 adhesion in Saskatchewan. In addition, the Alberta and Saskatchewan Commission of 1900 settled outstanding claims produced after the 1899 announcement that ‘half-breeds’ born between 1870 and 1885 were eligible for scrip, too, and also dealt with outstanding treaty 8 claims. In all, 24,326 claims were approved by 1929.29Scrip, then, was a major undertaking in Canadian history, and its importance as both an Aboriginal policy and a land policy should not be overlooked.

Sources Consulted / Further Reading

- Augustus, Camie. "The Scrip Solution: The North West Métis Scrip Policy, 1885-1887," MA Thesis, University of Calgary, 2005

- Canada. Historical Treaties of Canada, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Lands Directorate. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/trts/hti/site/mpindex_e.html.

- Corrigan, S. and J. Sawchuk, eds. The Recognition of Aboriginal Rights. Brandon: Bearpaw Publishing, 1996.

- Ens, Gerhard. Homeland to Hinterland: The Changing Worlds of the Red River Métis in the Nineteenth Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996.

- Ens, Gerhard. "Taking Treaty 8 Scrip, 1899-1900: A Quantitative Portrait Of Northern Alberta Métis Communities," Lobstick v.1, n.1 (2000), p. 229-258.

- Flanagan, Thomas. Métis Lands in Manitoba. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1991.

- Flanagan, Thomas. "The Market for Métis Lands in Manitoba: An Exploratory Study," Prairie Forum vol. 16, no. 1 (1991), p. 1-20.

- Hatt, Ken. "North-West Rebellion Scrip Commissions, 1885-1889," in F. Laurie Barron and James B. Waldram, eds., 1885 and After: Native Society In Transition. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1986, p. 189-204.

- Madill, Dennis F.K. Treaty Research Report: Treaty Eight (1899) (Ottawa: Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1986.

- Métis National Council, "A Guide to the Northwest ‘Half-breed’ Scrip Applications Document Series," Métis National Council Historical Online Database http://tomcat.sunsite.ualberta.ca/MNC/learn.jsp.

- Milne, Brad. "The Historiography of Métis Land Dispersal, 1870-1890," Manitoba History, 30 (Autumn 1995), p. 30-41.

- Murray, Jeff. "Métis Scrip Records," Government Archives Division, National Archives of Canada. Ottawa: 1986

- Ray, Arthur J., Jim Miller, and Frank J. Tough. Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000.

- Sawchuk, Joe, et.al. Métis land Rights in Alberta: A Political History. Edmonton: Métis Association of Alberta, 1981.

- Sprague, D.N. Canada and the Métis, 1869-1885. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 1988.

- Taylor, John Leonard. "An Historical Introduction to Métis Claims in Canada," The Canadian Journal of Native Studies 3, 1 (1983), p. 151-181.

- Tough, Frank. "As Their Natural Resources Fail": Native Peoples and The Economic History Of Northern Manitoba, 1870-1930. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1996.

- Tough, Frank. "Métis Scrip Commissions: 1885-1924," in Ka-iu Fung, ed., Atlas of Saskatchewan. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan Bookstore, 1999, p. 62.

Notes

1. Parts of this essay are based on my MA thesis: see Camie Augustus, "The Scrip Solution: The North West Métis Scrip Policy, 1885-1887," MA Thesis, University of Calgary, 2005. back

2. Canada Sessional Papers 1886, Vol. XIV (No. 45), Department of the Interior, p. 10-28. back

3. Canada, Statutes, Vic. 42, Cap. 31, Sec. 125(e). [Dominion Lands Act, 1979]. back

4. A.M. Burgess to W.P.R. Street, 30 March 1885 (NAC MG 29, Series E16, Volume 1, File3). back

5. A letter sent in 1885 to J.R. Burpé, Secretary of the Dominion Lands Commission in Winnipeg illuminated this point. The concern expressed, according to Burpé, was if claimants would have to "undergo a heavy, long, or expensive journey" to reach the commission. Burpé to Street, 12 June 1885 (NAC MG 29 E-16, Vol. 1, File 4). Another letter written by David Macarthur on behalf of Métis at Lakes Manitoba and Winnipegosis supports this point. Although a commission had been sent to Winnipeg to hear their claims previously, he noted "that only a few were able to attend and that the others by reason of poverty and other causes were unable to do so." David Macarthur to Secretary, Department of Interior, 3 October 1885 (NAC RG 15, D-II-3, Vol. 178, File HB 1104). back

6. See for instance Frank Tough, "As Their Natural Resources Fail": Native Peoples and The Economic History Of Northern Manitoba, 1870-1930 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1996). For a contrary view, see Thomas Flanagan, Métis Lands in Manitoba (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1991). back

7. Métis National Council, "A Guide to the Northwest ‘Half-breed’ Scrip Applications Document Series," Métis National Council Historical Online Database (http://tomcat.sunsite.ualberta.ca/MNC/learn.jsp, retrieved March 2008). back

8. Outside of Saskatchewan, scrip commissions also ran in conjunction with Treaty 11. For a history of these and other treaties, see Arthur J. Ray, Jim Miller, and Frank J. Tough, Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000). back

9. Dennis F.K. Madill, Treaty Research Report: Treaty Eight (1899) (Ottawa: Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1986). back

10. Statutes of Canada, Vic. 62-63, Cap. 16, Sec. 4. back

11. Jeff Murray, "Métis Scrip Records," Government Archives Division, National Archives of Canada (Ottawa: 1986). back

14. Métis National Council, "A Guide to the Northwest ‘Half-breed’ Scrip Applications Document Series," Métis National Council Historical Online Database (http://tomcat.sunsite.ualberta.ca/MNC/learn.jsp, retrieved March 2008). back

15. Two perspectives have emerged in the secondary literature regarding the history of the scrip policy. One camp, led mainly by historian D.N. Sprague and sociologist Ken Hatt, asserts that the scrip policy was ill-conceived and poorly administered, and ultimately dispossessed or defrauded the Métis of their lands. The other side, represented largely by political scientist Thomas Flanagan and historian Gerhard Ens, argues that this was not the case: the government was well-intentioned and the Métis sale of land was their own rational choice. See bibliography for references. back

16. Tough, As Their Natural Resources Fail. back

17. W.P.R. Street, "The Commission Of 1885 To The North-West Territories," Canadian Historical Review, with Introduction by H.H. Langton, vol. 25, no. 1 (1944). back

18. For discussions on this topic, see Gerhard Ens, Homeland to Hinterland: The Changing Worlds of the Red River Métis in the Nineteenth Century (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996); "Métis Scrip," in S. Corrigan and J. Sawchuk, eds., The Recognition of Aboriginal Rights (Brandon: Bearpaw Publishing, 1996), p. 47-57; and Thomas Flanagan, "The Market for Métis Lands in Manitoba: An Exploratory Study," Prairie Forum 16, 1 (1991), p. 1-20. back

19. Memorandum for Mr. Newcombe, 14 October 1921 (NAC RG 13, Vol. 2170, File 1853 [1921]). back

20. Canada, Statutes, 1870, 33 Vic., Cap. 3, sec. 31 [The Manitoba Act]. back

21. Canada, Statutes, 1883, 46 Vic., Cap.17, Sec. 81(e) [Dominion Lands Act 1883]. back

22. Privy Council OPCP 898, 9 May 1887. This order authorized the extension of the NWHB Commission and outlined the commission’s jurisdiction as "those portions of the Territories since ceded by the Indians under treaty with the Government of Canada." Although Section 3 of the 1883 Dominion Lands Act set out this limitation, this was the first mention in the orders-in-council confining the jurisdiction of scrip commissions to ceded Indian territory. However, a reference was first made in 1886 in a draft letter of instructions to Goulet from Burgess, 17 May 1886 (NAC RG 15, Vol. 501, File 140862). back

23. Privy Council OPCP 918, 6 May 1899. back

24. Jeff Murray, "Métis Scrip Records," Government Archives Division, National Archives of Canada (Ottawa: 1986). back

25. Joe Sawchuk, et.al. Métis land Rights in Alberta: A Political History (Edmonton: Métis Association of Alberta, 1981), p. 80. back

27. Frank Tough, "As Their Natural Resources Fail": Native Peoples and The Economic History Of Northern Manitoba, 1870-1930 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1996) p. 114. back

29. Côté Report, 1929. Link to database ID 24779 (no image). back