'He Scarcely Resembles the Real Man': images of the Indian in popular culture

Author: Brendan Frederick R. Edwards

Indians, as most non-Aboriginal people think they know them, do not exist. Historian Daniel Francis states that "The Indian began as a White man's mistake, and became a White man's fantasy. Through the prism of White hopes, fears and prejudices, indigenous Americans would be seen to have lost contact with reality and to have become 'Indians'; that is, anything non-Natives wanted them to be."3 Through non-Aboriginal writing, theatre, film, television, comic books, and advertising, Indians have existed as the invention of the European. As such, the popular conception of the Indian has resulted not in accurate representation, but rather an often insulting and misinformed caricature. Teepees, headdresses, totem poles, birch bark canoes, face paint, fringes, buckskin, and tomahawks have thus become the universal symbols of "Indianness," and such monikers as "Injun," "redskin," "squaw," "savage," and "warrior," have too often been used to label Aboriginal characters.4 As the curators of the 1992 touring museum exhibit, "Fluffs and Feathers" noted, these "are the symbols that the public uses in its definition of what an Indian is. To the average person, Indians, real Indians, in their purest form of 'Indianness,' live in a world of long ago where there are no high-rises, no snowmobiles, no colour television. They live in the woods or in mysterious places called 'Indian Reserves.'"5 These Indians are the Indians of storybooks, novels, films, that most non-Aboriginal North Americans were exposed to as children and in school. To many contemporary non-Aboriginal people, Indians are no more real than characters of fantasy; they are characters of the imagination, role-played by countless non-Aboriginal children (and adults) in school playgrounds, as Boy Scouts and Girl Guides.

Symbols of Indianness have largely been constructed and imagined by non-Aboriginal people, resulting in the use of such images as mascots of professional and non-professional sporting teams (the Atlanta Braves, Chicago Blackhawks, Cleveland Indians, Edmonton Eskimos, Washington Redskins, etc.), as the logos of high-profile brand marketing and promotional materials of any number of consumer goods and events, from automobiles (Pontiac), to the Canadian Pacific Railway (in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries), to the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics (although not technically considered "Indians," images of Inuit culture, formerly known as the Eskimo, are equally appropriated and mis-represented by non-Aboriginal cultures. The Vancouver Olympics has appropriated an Inuit inuksuk as part of its advertising scheme) and even the nation of Canada itself (postcards and trinkets aimed at international tourists are blanketed with images of Indians and Inuit). As caricatures imagined by non-Aboriginals, such symbols of Indianness are immensely offensive to Aboriginal peoples.

European literary (mis)conceptions of the Indian

There have generally been two (mis)conceptions of the Indian since the time of Columbus and the invention of the printing press: the "Noble Savage" (this conception includes the Indian Princess) and the "bloodthirsty" villain (including the intoxicated Indian and easy squaw). These images, of the good and bad Indian, have been so strong and deeply held by non-Aboriginal cultures so as to have persisted virtually unchanged since 1493.6 Very soon after Columbus' "discovery," as information about the new world was dispersed and became more widely known in Europe, Aboriginal peoples became a permanent fixture in the literary and imaginative works of Old World writers and popular storytellers.

Such (mis)conceptions were not limited to popular culture, but were also accepted norms for generations within the halls of academia. One could argue, in fact, that the cigar shop Indians of the twentieth century were born of academic misconception centuries earlier. The voluminous Jesuit Relations, for example, provided the French, and in turn other European scholars, a basis on which eighteenth-century deists and philosophers could draw in their moral and political writings.

Extracts from the Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1679 (image details) |

Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot, among others, used the conception of the enlightened Noble Savage to critique French and European societies and social institutions of the day. The idea of the Noble Savage, for European philosophers and critics, represented the possibility of progress by "civilised" society if allowed the freedom to escape outworn social institutions.7 By the end of the eighteenth century, the Noble Savage convention had become so widely used to criticize European institutions that the supporters of those institutions were compelled to attack the conception of the enlightened Noble Savage, often evoking the other idea of the Indian, the bloodthirsty villain.

The idea of nobility, in relation to new world peoples, could be seen in how Aboriginal people were often depicted in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries: for the most part, they were described as part of the North American environment, something which European colonists had to overcome in their cause of progress and the task of nation-building. So harmonious was the relationship between the Indian and nature that outsiders viewed the two elements as an integrated part of the new world. Thus, Euro-Americans and Euro-Canadians felt a need to conquer and dominate Aboriginal peoples (and their environment) and to remould them in old world conceptions. As historian Cornelius Jaenen explains in relation to French-Aboriginal relations, "it was the French who sailed to America and established contact with the aborigines, not the Micmacs or Iroquois who sailed to Europe and established contact with the Bretons, Normans and Rochelais."8 Therefore, in European ideology of the time, Europe was assumed to be the centre of the world and civilisation, and its cultures more advanced and older than the cultures of other parts of the world. Such Eurocentrism permeated the old world's understandings of the new world and the relationships that were forged there. The myth of the Noble Savage, and its binary opposite, the depraved barbarian, were thus present in all cultural contact between Europeans and North American Indians. Although such views were a polarization, they coexisted. When European cultures were dependent on Aboriginal peoples for safety and sustenance, the dominant view of Indians was that of the Noble Savage. But when Indians got in the way of proposed European settlement or "progress," or sided with a competing European competitor or enemy, then Aboriginal people were portrayed as barbarian and savage. Jaenen, in the context of French-Aboriginal relationships, describes the French view of Indians as both friend and foe, depending entirely upon the immediate circumstances.9

Of course, the very basis of what is "civilized" and what is "savage" is entirely unclear. Eurocentric attitudes and assumptions lead Euro-North Americans to assume that the cultures of Europe were the pinnacle of civilization and that Aboriginal new world cultures stood in opposition to this. Yet, as the historian and journalist Olive Patricia Dickason explains, "The word 'civilized' is usually applied to societies possessing a state structure and an advanced technology…. The term 'savage' is applied to societies at an early stage of technology, a stage at which they are believed to be dominated by the laws of nature. Its use implies that Amerindian societies did not match the refinements of those of Europe, and that they were more cruel."10 But as she goes on to elucidate, neither premise stands up under close examination: to suggest that Peruvians or Mexicans, for example, lacked sophistication is absurd. Clearly they (and other Indigenous North American societies) were highly developed, but their value systems were clearly very different from those of the French, English, or Spanish. To say that Aboriginal peoples were crueller also fails to stand up to examination – on both sides of the Atlantic public executions were practiced. Thus the classification of Aboriginal peoples as savage was a conscious tactic by which Europeans were able to create the ideology that helped make colonization of the new world possible.11

The French and American Revolutions inspired the conception of the Noble Savage as a critique on the social ills of the day. But by the nineteenth century a more romantic, rather than enlightened, image of the Noble Savage took hold in the arts and literature. In England, the conception of the romantic Noble Savage was best expressed in Thomas Cooper's long poem, Gertrude of Wyoming (1809),12 the first popular English poem set in North America and including Aboriginal characters. In France, François-René de Chateaubriand published, Atala, ou les amours de deux sauvages dans le desert (1801).13 Both works imagined picturesque and mysterious landscapes, combined with the confrontation of the "civilised" and "savage." Each volume was published in several editions, producing a romantic and primitive image of the Indian that would speak to generations of Europeans. The successes of these literary works encouraged other European writers to draw on the new world for "picturesque people and sublime nature."14 In an 1884 introduction to the English translation of Atala, Edward J. Harding expresses a familiar tone, noting that the "red Indian" has all but vanished and been forgotten; "to-day the red man's war whoop resounds only in literature of the 'dime novel' school. But it was not so in 1801, the year that witnessed the publication of 'Atala'….After all, who knows how the primitive red Indian thought and spoke? Certainly Chateaubriand is not alone in representing him as courteous, eloquent, tinged with sentiment…."15 Chateaubriand himself describes Chactas, Atala's lover, as "a savage more than half civilized, since he knows not only the living but also the dead languages of Europe. He can therefore express himself in a mixed style, suitable to the line upon which he stands, between society and nature."16 The character of Atala, similarly, is that of a half-Indian princess whose love for Chactas cannot be realized because she is Christian and he is not. Told as a quasi-Homeric narrative, Atala was embraced as an exciting and exotic piece of literature when it was published in 1801. Its "strange blend of primitive 'Homeric' simplicity and a brooding Romantic melancholy," as David Wakefield notes, "set the fashion for literary heroes and their pictorial counterparts for the next half century."17 Atala served as a major influence in the work of several artists and writers in the nineteenth century, such as the French painter, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767-1824), whose famous piece, The Burial of Atala, was first exhibited in 1813.18

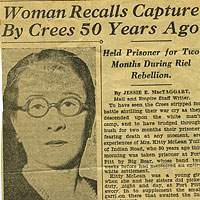

Following the American Revolution, a similar imaginative transformation of Aboriginal peoples took place, from the Indian of contact to a mythic and symbolic Indian. Like the European conception of the Indian, the American literary idea of Aboriginal peoples was one part romantic and enlightened Noble Savage who stood for the potential freedoms of humankind, and conversely, the bloodthirsty villain that stood in the way of progress and manifest destiny. The nineteenth century saw an explosion in the popularity of captivity narratives, many of which were bestsellers. All included the basic premise of the pains and horrors that Euro-North Americans suffered under the enslavement of Aboriginal peoples. Obviously, the bloodthirsty villain conception of the Indian prevailed, but more importantly the captivity narratives reached readers from both high and low cultures. The best known of the captivity narratives was Samuel Drake's, Indian Captivities; Or life in the wigwam, first published in 1839.19 Canadian captivity titles from this era included Theresa Gowanlock's, Two months in the camp of Big Bear (1885), John R. Jewitt's, The Adventures and sufferings of John R. Jewitt (1824), and Samuel Goodrich's, The Captive of Nootka (1835).20 The sensationalism and violence of these commercially-geared texts were a direct influence and precursor to the popular dime novels and cowboy and Indian movies of the early twentieth century.21

Yet, "captivity," in the words of historian John Demos, "meant 'contact' of a particularly vivid sort."22 In other words, captivity narratives were, at their heart, stories of the encounter between Euro-North Americans and Aboriginal peoples. So while they may have been sensationalised, and certainly fictionalised, they said something of the innermost feelings of Euro-North Americans towards Aboriginal cultures. They portrayed a very real sense of fear, of difference (and attempts at bridging or eliminating difference), and most of all they usually maintained a Eurocentric point of view, assuming Indians to be inherently, if not forever unredeemable. At the heart of captivity narratives was the interplay and conflict between "civilization" (i.e., the European newcomers, who were normally the authors of such texts) and "savagery" (the Indians). Historian Sarah Carter notes that captivity narratives served to construct (and maintain) a perceived threat posed by Indians to "civilized" Euro-Canadian behaviour, particularly in relation to the honour of white women, and to maintain the need to pursue strategies of exclusion and control. Such stories (real or imagined) fed newcomer fears that Aboriginal people (mainly predatory males) were lying in wait to pounce on white children (usually girls) and spirit them away. Captivity narratives, therefore, served as literary barriers, segregating Euro-North Americans (the writers and readers of such stories, overwhelmingly) from Aboriginal populations. They created and fed into an "us versus them" mentality, buttressing (often false) stereotypical images of Indians and European women as a means of establishing social and spatial boundaries between settlers and Aboriginal peoples, and to justify repressive measures against Indian populations.23

Newspaper and media reports in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century glorified and fed a kind of hysteria about Aboriginal people capturing Euro-Canadians, particularly women. In several cases, newspaper reports actively made-up stories about white women who had been subject to "nameless horrors of Indian indignity and savage lust," when in reality the women suffered little and in some cases had actively chosen to stay amongst their Aboriginal friends. In other words, they could hardly be called captives at all.24 Carter, provides examples of such stories and women, particularly those of Theresa Delaney and Theresa Gowanlock, who were reportedly held captive and subjected to horrors in Big Bear's camp at Frog Lake during the North-West Resistance of 1885, and the McLean sisters who were resident amongst the Plains and Woods Cree for two months during the Resistance that same year.

Particularly interesting is Carter's exploration of the case of Amelia McLean Paget (1867-1922). The daughter of a prestigious Scottish fur trader and a Métis mother, she and her sisters lived in close contact with the Plains Cree and Saulteaux during a time that included the disappearance of the buffalo, the North West Resistance, and the establishment of the reserve system in the prairie west. Along with her mother and sisters, McLean Paget was something of a celebrity during the 1885 Resistance, when the family spent two months with the Plains Cree chief Big Bear and a mobile group of Plains and Woods Cree, and was involved in three violent confrontations at Fort Pitt, Frenchman Butte, and Steele's Narrows. During their months with the Cree, newspapers circulated rumours that the McLean sisters were being mistreated as "slaves of the lesser chiefs" and that they had suffered the "final outrage."25 But, as Carter notes, "they were not…the objects of the same level of frenzied attention that was directed toward the two White widows of Frog Lake, Theresa Delaney and Theresa Gowanlock."26 Carter attributes the different tone in the media reports to the fact that the McLean sisters did not fit the prevailing stereotype of Euro-Canadian women as weak, vulnerable, and passive. On the contrary, the McLean sisters were resilient and resourceful, demonstrating keen shooting skills, courage, and independence. Additionally, the McLean's were also of Aboriginal heritage (although the McLean's themselves did not identify closely with this part of their familial history) so their need to be valiantly rescued was thus complicated.27 In truth, the McLean sisters were not "captive" at all, but chose to stay amongst the Cree, despite the dangers they knew they would face. Although newspapers initially tried to paint the McLean sisters as victims, they eventually did not know how to depict these strong, independent, and resourceful women.

Some decades later, in 1909, Amelia McLean Paget (by then she was married to Department of Indian Affairs bureaucrat Frederick Paget)28 published a book called The People of the Plains, based on observations and interviews she had been commissioned (by the Department of Indian Affairs) to undertake amongst the scenes of her childhood and the reserves of the Cree, Saulteaux, and Assiniboine. Her manuscript was edited and presented to a publisher by Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs (and poet), Duncan Campbell Scott. Despite Scott's editing, The People of the Plains is a sympathetic appreciation of Aboriginal plains culture, challenging conventional views. Paget dispelled myths of plains women as overworked and overburdened, even going so far as saying the women agreed and were happy in polygamous relationships. Researching and writing at a time when the Indian Act banned such activities as the sun dance, when the mothering and housekeeping skills of Indian women were heavily criticized in government publications as a means of justifying the residential school system, and when traditional chiefs were being overthrown by government policy because of their beliefs and practices, Paget "threatened powerful conventions and proposed a radical departure from prevailing wisdom."29 This is all the more remarkable when we consider that her husband was a respected Indian Affairs bureaucrat, and that Duncan Campbell Scott edited and oversaw the publication of her work.

It is not known to what degree Scott altered Paget's original manuscript, but it is telling that he felt compelled to offer details of Paget's background in his 1909 introduction to the book. Scott characterised Paget as being overly positive in her description of Aboriginal peoples because of her capture at Fort Pitt by Big Bear and his camp. Describing Paget as a "cordial advocate," Scott suggested that her memory of the events had obviously been heightened and romanticised over time. Although Scott was apologetic to readers for Paget's positive portrayals of plains life, Carter notes that this stands in stark contrast to the role of Delaney and Gowanlock who years earlier had been required to be "frigid critics" of the western tribes. In large part, Carter attributes Paget being allowed to act as a "cordial advocate" because in 1909 the Indians of the plains were no longer considered to be a threat; they were instead viewed as a weak and waning race.30 Despite the fact that Paget's book received favourable reviews when it was published, indicating there were other Euro-Canadians sympathetic to her views, negative depictions of Aboriginal peoples still prevailed in media and Euro-Canadian writing of the early twentieth century.

Duncan Campbell Scott, now notoriously associated with his administration of Indian Affairs, was during his lifetime (1862-1947) widely celebrated as one of Canada's Confederation Poets. 31 Although Scott felt he was critically neglected as a poet, his literary reputation has been solid since at least 1900, with his work appearing in virtually all major anthologies of Canadian poetry.32 Scott's day job however, as a leading administrator and architect of policy at Indian Affairs, has come to define the man more than his poetry. His tenure as Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs was a turbulent one, characterised by a paternal and narrow approach to administering affairs relating to Aboriginal health, education, and welfare. Rather ironically, much of his poetry was related to "Indians." Drawing on his experience as an Indian administrator in the field, Scott expressed sensibilities as a poet saddened by the perceived waning of ancient Aboriginal culture (i.e. the "vanishing Indian"). Yet in his administrative work, Scott actively sought to assimilate Indians into the Canadian mainstream, effectively quickening the pace of the demise he felt was so imminent.

Perhaps this was a strategy on Scott's part. If he could render the idea of Indians firmly to the past through his work as an administrator in Indian Affairs, then maybe his Indian poetry would be taken more seriously. In all likelihood, however, Scott truly believed that the only "authentic" Indian was a pre-contact Indian. In other words, Scott perceived the Indian of the past as a "noble savage," and the Indian of the present as merely in the way of progress.33

Although widely respected as a literary man in his day, Scott's reputation as a writer did nothing to help the aspiring literary careers of early twentieth century Aboriginal writers. Evidence shows that he very nearly single-handedly quashed the aspirations of (today largely unknown) Aboriginal writers like Anglican priest, Edward Ahenakew (Plains Cree) and Indian Affairs employee, Charles A. Cooke (Mohawk). Cooke attempted to start an "Indian National Library" within the Department of Indian Affairs in 1904, envisioning a collection of rare books and reports which could be accessed by departmental officials of course, but also members of the public and Aboriginal peoples themselves. Although he found widespread outside support for such an endeavour, the idea was stopped dead in its tracks by Scott who saw no value in the proposal. Other literary projects begun by Cooke, including an unprecedented study of Iroquois languages and a newspaper in Mohawk, were tackled without any support from Scott or the Department of Indian Affairs.

Edward Ahenakew in 1922, with the help of academic and literary acquaintances, submitted a manuscript to Ryerson Press relating to stories he had compiled through conversations with Chief Thunderchild. Noted cultural nationalist and publisher, Lorne Pierce, was then chief editor at Ryerson Press, and he considered Ahenakew's manuscript to be of considerable interest and value. But unfortunately for Ahenakew, and other Aboriginal authors of the day, Ryerson Press was in financial difficulties in the early 1920s. Under such circumstances Pierce sought financial subvention to publish Ahenakew's work. Not surprisingly, Pierce approached the Department of Indian Affairs for financial assistance. In his response to Pierce's request for financial assistance, Scott wrote, "I regret very much that we would have no funds to meet your suggestion with reference to Mr. Ahenakew's manuscript, much as I would like to assist."34

A Vanishing Race

Both the romantic and savage images of the Indian were popular in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century literature, dime novels, and comic books. And most romantic of all was the notion that Aboriginal peoples were rapidly disappearing. The vanishing race conception was embraced and wholly believed by not only the average European or North American reader, but also by the Canadian and American federal governments who administered policy relating to Indians. As a literary device, the idea of a vanishing race before the onslaught of "civilisation" inspired in audiences feelings of nostalgia, pity, and tragedy. As Berkhofer, Jr. notes, "the tragedy of the dying Indian, especially portrayed by the last living member of a tribe, became a staple of American literature."35 The most famous of this genre was, of course, James Fenimore Cooper's, The Last of the Mohicans, originally published in 1826, and still considered a classic by contemporary audiences and scholars.36 But Cooper's so-called masterpiece was only one of forty such novels published in the United States between 1824 and 1834 which included Indian episodes and portrayed Aboriginal cultures as vanishing. U.S. literary historian, G. Harrison Orians, noted that several of these novels could have been titled "The Last of…" as all, to various degrees, tapped into a sense that Indians were fleeting figures on the North American landscape.37 In time they would either die out, or become fully assimilated into the fabric of Euro-North American society.

Combined with the idea of the vanishing race, the Noble Savage in literature and art was generally only found in the "wild west," beyond the corruption of advancing Euro-American and Euro-Canadian "civilisation." Thus, eventually the Aboriginal peoples of the Plains became, in the minds of most European and Euro-North American readers and authors, the quintessential "Indian." And as the west was won, so to speak, or settled and "civilised" by Euro-Canadians and Americans, the Noble Savage, and thus the Indian, came to be seen as safely dead and historically past in the minds of most. Poets and writers, such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (The Song of Hiawatha, published in 1855), thus began to romanticise the safely dead Indian.38 The main theme of such literature was the battle between savagery and civilisation, with the too often inevitable outcome of "civilisation" triumphing. In these stories, Indians, both noble and savage, were eventually eliminated through disease, alcohol, war, or simply the passage of time. Books and poems sharing these sentiments were widely read and enormously influential, with their themes spilling over into film, radio, television, and even school textbooks. The image of the Noble Savage or bloodthirsty Indian villain was not merely literary, but also a staple of popular culture.

Thus, the Indian of reality was eliminated, in the eyes and minds of many, by the printing press, the stroke of a pen, and the turn of the page. Much like Edward Said's theory of Orientalism, Euro-Canadian and Euro-American print cultures helped to define the new world by creating Aboriginal peoples as "the other."39 Widespread literacy and publishing by a non-Aboriginal populace effectively vanished the Indian of reality.40 Historian Brian Dippie has argued that the "vanishing American" has been a constant in Euro-American thinking since at least the early nineteenth century, becoming something of a self-perpetuating cultural myth. In Dippie's words, "It was prophecy, self-fulfilling prophecy, and its underlying assumptions were truisms requiring no justification apart from periodic reiteration…. The point was no longer whether or not the native population had declined in the past but that its future decline was inevitable. The myth of the Vanishing American accounted for the Indians' future by denying them one, and stained the tissue of policy debate with fatalism."41

Karl May and the Modern European Image of the Indian Other

Through the first half of the twentieth century, the Federal government's explicit goal was to transform the Indian into a productive individual and respectable citizen through the vehicles of religion and education. The ultimate effect of more than 100 years of a policy of civilisation and assimilation did not succeed in eliminating Aboriginal peoples, as the government planned, but it did succeed, in many ways, in eliminating the Indian from the Euro-Canadian public consciousness. Increasingly pushed to the public and social backburner, Indians, in the minds of many Euro-Canadians, became caricatures of the representations they read about in popular fiction. In history textbooks of the day, Aboriginal peoples were mentioned usually within a paragraph or two at the beginning of the first chapter, and then they vanished. Perhaps the most influential and popular writers at that time, who employed Indians as their main subject or characters, were James Fenimore Cooper, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Karl May.

Ask almost any modern central or eastern European (particularly in those countries bordering Germany) what they know about North American Aboriginal peoples, and they will likely make some reference to Winnetou and the novels of the German fiction writer, Karl May. Although May did not visit North America or meet a real Indian until after he had done the bulk of his popular writing, his ideas and the imagined characteristics with which he designed his characters held popular in the European imagination for much of the twentieth century (and remain influential even today). A series of popular films, filmed in the former Yugoslavia, and featuring Slav and Italian actors, have assured the continued influence of May's books. His novels are still widely read and continue to be published in new editions in several languages. Young and old, male and female, enjoy May's stories. May's image of the Indian has inspired popular "Indian Hobbyist" clubs and activities, particularly in Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic.42 In the Slovak Republic, a popular reality TV programme featured an "Indian" character in the 2005-06 season. The audience and cast of Vyvoleni´ (similar to the American Big Brother programme) consisted overwhelmingly of young people, but middle-aged Jaroslav Marcinka, alias "Indian," was one of the programme's most popular characters.43

Indian Hobbyist clubs in Central and Eastern Europe are common. Participants not only dress like May's conception of Plains Indians, but also profess to live by "Indian values." Events vaguely resemble traditional Aboriginal pow-wows, featuring several teepees, wigwams, and sweat lodges. European hobbyists gather most of their information and ideas from the books of May, supplemented with details from anthropological and historical texts. More than simple fun, hobbyists take such events very seriously, often objecting to the scrutiny or observation of outsiders.

Although May's books are almost unheard of in North America today, their influence in Europe cannot be overstated. May's leading character was the young and brilliant German immigrant, Karl (or Charlie as he is initially called by his American friends), who travelled to St. Louis in search of adventure in the "Wild West." Seeking to be a true "Westman," Charlie demonstrates a natural and uncanny ability to quickly master all that he is taught (soon surpassing the talents of his teachers). Charlie's character demonstrates extraordinary strength and endurance, and he is soon christened "Old Shatterhand" by his Westerner colleagues because of his ability to fell men with only one blow. His physical strength is matched by a keen intellect and encyclopaedic knowledge, which Old Shatterhand has gained from books about the West. To other Westerners, Old Shatterhand's book learning is seen as silly and useless, but the German "greenhorn" always proveds them wrong. Old Shatterhand eventually gains the trust and friendship of Winnetou, the noble and powerful son of a Mescalero Apache chief. Under Winnetou's tutelage, Old Shatterhand enters "Indian School," where he is taught the ways of Indian life and becomes proficient in the Navajo and Apache languages.

In the character of Old Shatterhand, May portrays Germans as the pinnacle of enlightenment, civilization, and Christianity, and "as Old Shatterhand represents the highest ideal of the German nation, so Winnetou embodies the nobility to which the Native American can rise, assisted by enlightened whites."44 It is Winnetou's willingness to embrace the best of European (i.e. German) culture and blend it with the best qualities of his own culture, his ability to speak unaccented English, and to read and write which ennobles him.

Through the eyes of Old Shatterhand the Wild West is seen and distorted. May made no attempt to portray the West from a historical or anthropological reality. Throughout all of his books, May laments the retreat of the North American Aboriginal before the greed of American (i.e. not European) geographic, economic, and cultural imperialism. North American readers are accustomed to having North American heroes at the forefront in winning the West, but in Winnetou, the noble Teutonic/Apache duo always emerges triumphant over the inferior and villainous Yankee/American, "thereby inverting and subverting an almost sacrosanct myth and causing May's western books to ring strangely and falsely in the North American ear."45

Grey Owl's literary origins

Synonymous with Indians in Canada in the late 1920s and throughout much of the 1930s, was Grey Owl. Tremendously popular as an orator and writer internationally, Grey Owl was of course, not an Aboriginal person at all, but Archie Belaney, an Englishman. But not until his death in 1938 was Grey Owl's secret revealed. From the late 1920s until his death, Archie Belaney successfully presented himself as Grey Owl, the supposed son of an Apache mother and a Scots father who had been formally adopted by the Ojibwa of the Temagami district in Ontario. In his writing and speeches Grey Owl spoke with passion about the need to protect the Canadian wilderness and for fairer treatment of Canadian Indians. His wilderness message was wildly popular, spawning an early notion of environmentalism throughout North America and the United Kingdom. But his message with regards to Aboriginal peoples was not as well received, often falling on curious, but largely deaf ears. With the exception of Aboriginal peoples themselves, many of whom guessed Archie Belaney's secret, much of the world viewed Grey Owl as an "authentic" Indian. Prime Ministers, governors general, statesmen, literary figures, and other prominent individuals all bought into the idea of Grey Owl, and many initially refused to believe in the hoax once it was revealed upon his death.46

Belaney's popularity was due in part to his physiognomy: in other words, he fit the popular public conception of the noble savage, he looked precisely like a storybook Indian, as if he walked out of the pages of a James Fenimore Cooper or Karl May novel. Canadian literary historian, W.H. New, also attributes the public's widespread fascination with Grey Owl to "the continued public willingness to accept picturesque versions of wilderness life and native people as empirical realities."47 The public's willingness was directly related to the popularity of such writers as Ernest Thompson Seton, Cooper, May, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Donald Smith, in his biography of Grey Owl, notes that as an English boy, Archie Belaney devoured such books, idealising North American Indians: "He had never met one, or even seen one, but he had books about them. In the margins of these books he sketched feathered braves in buckskins – youthful drawings very similar to those he later used to illustrate his books. He longed to live amongst the noble red men of James Fenimore Cooper's and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's imaginations."48 As a schoolboy, Belaney regularly played Indians with his usually much less enthusiastic friends, modelling himself on the noble savages from his books. Grey Owl had a lifelong love of Longfellow's poem, Hiawatha, even using it as a learning tool in his efforts to speak Ojibwa, and he later modelled himself during his international speaking tours as the "modern Hiawatha."49 Belaney also read the stories and nature essays of Ernest Thompson Seton, and certainly showed familiarity with them in later life as Grey Owl, referring to Seton, for instance, in Tales of an Empty Cabin (1936). Belaney's childhood library included a copy of Seton's Two Little Savages (1903), the story of two young Euro-Canadian boys who choose to live as Indians. The boys discover Indians, of course, through books, and Seton's text would in turn influence a generation of North American and English children to act out their fantasies as Indians through woodcraft activities, and later, the Boy Scouts.

Young Archie Belaney's life in many ways mirrored that of Yan's, the central character in Two Little Savages: "Yan was much like other twelve-year-old boys in having a keen interest in Indians and in wild life, but he differed from most in this, that he never got over it. Indeed, as he grew older, he found a yet keener pleasure in storing up bits of woodcraft and Indian lore that pleased him as a boy."50

Grey Owl, who at the time was still considered an Indian (by non-Aboriginals, at least), was present at a Carlton, Saskatchewan celebration in honour of the signing of Treaty No. 6, in August, 1936. While the Plains Cree claim that it was at this ceremony that they knew once and for all that Grey Owl was not whom he claimed, another internationally famous writer was present at the Indian Diamond Jubilee celebrations. John Buchan, then known to Canadians as Lord Tweedsmuir, Governor General of Canada, was honoured at the Carlton ceremony by the Sweet Grass Band of Cree as "Chief Teller of Tales" (Okemow Otataowkew), partly for his role as governor general, representative of the Crown, but also in honour of his international fame and respect as an author. Tweedsmuir's honouring was witnessed by more than 5,000 spectators, and the ceremony included traditional gift giving and dancing.

Tweedsmuir showed a great interest in Grey Owl at the Carlton ceremony and agreed to visit him at his cabin in Prince Albert National Park in the future.51 Tweedsmuir met with Grey Owl, only a month later, and Grey Owl used that opportunity to secure as much help as he could for the Indians of Canada, proposing the idea that they should become official guardians of Canada's wildlife and forests. Tweedsmuir met officially with Grey Owl on at least two occasions as governor general, once in Ottawa in March, 1936, and at Grey Owl's cabin in Prince Albert National Park in mid-September 1936. One of Grey Owl's biographers, Donald Smith, writes that Grey Owl impressed the governor general and his family, playing the role of "Modern Hiawatha." Tweedsmuir is said to have greatly admired Grey Owl's remarkable knowledge of wildlife and the power of his writing in his books. At his cabin near Waskesiu, Saskatchewan, Grey Owl showed the governor general a beaver dam, trees felled by beavers, and beaver themselves. Grey Owl's accounts of that meeting indicate that Lord Tweedsmuir was an astute audience. He listened to Grey Owl's pleas for greater Indian sovereignty in Canadian life with apparent attention and sympathy.52 Tweedsmuir's personal correspondence confirms that he was a great fan of Grey Owl, as he repeatedly mentioned in his letters that he was looking forward to spending time with him in Prince Albert National Park. And when the time came, he was disappointed that bad weather cut his visit with Grey Owl short.53 Euro-Canadians, like Lord Tweedsmuir, believed whole-heartedly that Grey Owl was an authentic Aboriginal person, and Buchan's interest in Grey Owl was more than camaraderie between literary types.

As an articulate, literary "Indian" figure, Grey Owl fit the romantic notion of noble savage, and an example of an Indian partaking positively in civil society. His image was considered so authentic (before the truth was revealed) that often Aboriginal peoples (i.e. "real" Indians) of the day were not considered "Indian enough" unless they appeared publicly in buckskin and feathers, in full Indian garb. So entrenched in the popular public conscience was the noble savage, the feathered plains Indian standing stoic, that Alberta writer Robert Kroetsch could ironically observe in his 1973 novel, Gone Indian, that Grey Owl was "the truest Indian of them all."54

General public apathy and ignorance of how such inauthentic images misrepresent and offend Aboriginal peoples has allowed such old fashioned ideas to persist and be repeated, time and time again. Contemporary film, advertising, popular fiction (such as Harlequin romance novels, for instance), and television thus continue to falsely imagine Aboriginal peoples, and such images have altered remarkably little over the last 500 years. In recent years, Aboriginal peoples have begun to reclaim control of their own images. Aboriginal schools in the U.S. and Canada have thus begun to use their own symbols and mascots with Indian names and images. Aboriginal artists of all genres now employ stereotypical images ironically, in an effort to empower and assert control over their own image.

Suggested Further Reading

- Berkhofer, Jr., Robert F. The White Man's Indian: images of the American Indian from Columbus to present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978).

- Boehme, Sarah E., et. al. Powerful Images: portrayals of Native America (Seattle & London: Museums West and University of Washington Press, 1998).

- Deloria, Philip J. Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

- Dickason, Olive Patricia. The Myth of the Savage: and the beginnings of French colonialism in the Americas (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1984).

- Dippie, Brian W. The Vanishing American: White attitudes and U.S. Indian policy (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1982)

- Doxtator, Deborah. Fluffs and Feathers: an exhibit on the symbols of Indianness (Brantford ON: Woodland Cultural Centre, 1992).

- Francis, Daniel. The Imaginary Indian: the image of the Indian in Canadian culture (Vancouver: Arsenal Press, 1992).

- Haycock, Ronald Graham. The Image of the Indian: the Canadian Indian as a subject and a concept in a sampling of the popular national magazines read in Canada 1900-1970 (Waterloo ON: Waterloo Lutheran University Press, 1971).

- Jaenen, Cornelius J. Friend and Foe: aspects of French-Amerindian cultural contact in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976).

- Sheffield, R. Scott. The Red Man's on the Warpath: the image of the "Indian" and the Second World War (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004).

Notes

1. Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr. The White Man's Indian: images of the American Indian from Columbus to present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978) 71.L back

2. Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle (1933; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978) 227-228. back

3. Daniel Francis, The Imaginary Indian: the image of the Indian in Canadian culture (Vancouver: Arsenal Press, 1992) 5. back

4. See: Viki Ann Green, The Indian in the Western Comic Book: a content analysis (Master of Education thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1974). back

5. Deborah Doxtator, Fluffs and Feathers: an exhibit on the symbols of Indianness (Brantford ON: Woodland Cultural Centre, 1992) 10. back

6. See: Berkhofer, Jr. 71-111, which discusses the image of the Indian in literature, art, and philosophy. back

7. See, for example, Roger L. Emerson, "American Indians, Frenchmen, and Scots philosophers," Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 9 (1979) 211-236; Paul Honigsheim, "Voltaire as Anthropologist," American Anthropologist XLVII (1945) 104-118; Honigsheim, "The American Indian in the Philosophy of the Enlightenment," Osiris X (1952) 91-108; Carla Mulford, "Benjamin Franklin, Native Americans, and European cultures of civility," Prospects 24 (1999) 49-66. back

8. Cornelius J. Jaenen, Friend and Foe: aspects of French-Amerindian cultural contact in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976) 10. back

10. Olive Patricia Dickason, The Myth of the Savage: and the beginnings of French colonialism in the Americas (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1984) xi. back

12. Thomas Campbell, Gertrude of Wyoming, a Pennsylvania tale, and other poems (London: Bensley, 1809). back

13. François-René de Chateaubriand, Atala, or, The love and constancy of two savages in the desert. Caleb Bingham, trans. William Leonard Schwartz, ed. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1930). back

14. Berkhofer, Jr. 79-80. back

15. Edward J. Harding, "Introduction," Atala: by Chateaubriand. Trans. by James Spence Harry. Illust. by Gustave Doré (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1884) 7, 8, 9. back

16. Chateaubriand, "Preface to the First Edition," Atala: by Chateaubriand. Trans. by James Spence Harry. Illust. by Gustave Doré (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1884) 17. back

17. David Wakefield, "Chateaubriand's 'Atala' as a Source of Inspiration in Nineteenth-Century Art," The Burlington Magazine 120.898 (1978) 13-24. back

18. See: "Girodet: Romantic Rebel." February, 2006. The Art Institute of Chicago. 21 January, 2008, <http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/girodet/>. back

19. Samuel G. Drake, Indian Captivities; Or Life in the Wigwam: being true narratives of captives who have been carried away by Indians, from the frontier settlements of the United States, from the earliest period to the present time (1839; Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1854). back

20. Theresa Gowanlock, Two months in the camp of Big Bear: the life and adventures of Theresa Gowanlock and Theresa Delaney (Parkdale: Times, 1885); John Rogers Jewitt, The Adventures and sufferings of John R. Jewitt, the only survivor of the ship Boston, during a captivity of nearly three years among the savages of Nootka Sound: with an account of the manners, mode of living and religious opinions of the natives (Edinburgh: Archd. Constable & Co., 1824); Samuel G. Goodrich, The Captive of Nootka, or, The adventures of John R. Jewitt (New York: J.P. Peaslee, 1835). back

21. For more on the Indian captivity genre, see: Pauline Turner Strong, Captive selves, captivating others: the politics and poetics of colonial American captivity narratives (Boulder: Westview Press, 1999); Rebecca Blevins Faery, Cartographies of desire: captivity, race, and sex in the shaping of an American nation (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999); Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola and James Levernier, The Indian captivity narratives, 1550-1900 (Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan, 1993); Sarah Carter, Capturing women: the manipulation of cultural imagery in Canada's Prairie West (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1997); Gordon M. Sayre, ed., American Captivity narratives: selected narratives with introduction (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000). back

22. John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: a family story from early America (1994; London: Papermac, 1996) xii. back

24. Quoted in Carter 87. Carter provides examples, particularly the stories of Theresa Delaney and Theresa Gowanlock, who were reportedly held captive and subjected to horrors in Big Bear's camp at Frog Lake in 1885. back

25. Quoted in Sarah Carter, "Introduction to the 2004 Edition: The 'Cordial Advocate': Amelia McLean Paget and The People of the Plains" In Amelia M. Paget, The People of the Plains (1909; Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center and the University of Regina, 2004) xvi. See also: Sarah A. Carter, "The 'Cordial Advocate': Amelia McLean Paget and The People of the Plains" In With Good Intentions: Euro-Canadian and Aboriginal relations in colonial Canada. Ed. by Celia Haig-Brown and David A. Nock (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2006) 199-228. back

26. Carter "Introduction" xvi. back

27. Carter, "Introduction" xvi-xvii. back

28. Frederick Paget was employed by the Department of Indian Affairs in Regina as assistant to Indian commissioners Hayter Reed and Amedee Forget from 1882-1899. In 1899, the same year he married Amelia McLeod, he was appointed chief accountant of the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa. Sarah Carter reports that although he was an accountant, he was valued for his advice on western Indians, in part due to his wife's background. He was also the author of a 1908 report on residential schools in the west which was highly critical. See: Carter, "The 'Cordial Advocate'" 212-213. For discussion of Frederick Paget's 1908 report, see: John S. Milloy, "A National Crime": the Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1999) 82-83. back

29. Carter, "Introduction" xxvi. back

30. Carter, Capturing Women 121-123. back

31. For more on Duncan Campbell Scott as an administrator of Indian Affairs, see E. Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1986). back

32. For more on Scott's literary achievement, see: Stan Dragland, ed., Duncan Campbell Scott: a book of criticism (Ottawa: Tecumseh Press, 1974); Dragland, Floating Voice: Duncan Campbell Scott and the literature of Treaty 9 (Concord ON: Anansi, 1994); Gordon Johnston, Duncan Campbell Scott and his works (Downsview ON: ECW Press, 1983); R.L. McDougall, "Scott, Duncan Campbell" The Canadian Encyclopedia (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1999) 2121. back

33. For discussion of Scott's Indian poetry specifically, see: D.M.R. Bentley, "Shadows in the Soul: racial haunting in the poetry of Duncan Campbell Scott" University of Toronto Quarterly 75.2 (2006) 752-770; Dragland, Floating Voice; Gerald Lynch, "An Endless Flow: D.C. Scott's Indian poems" Studies in Canadian Literature 7.1 (1982) 27-54: Lisa Salem-Wiseman, "'Verily, the White Man's Ways Were the Best': Duncan Campbell Scott, Native culture, and assimilation" Studies in Canadian Literature 21.1 (1996) 120-142; and L.P. Weis, "D.C. Scott's View of History and the Indians" Canadian Literature 111 (1986) 27-40. back

34. Queen's University Archives, Lorne and Edith Pierce Collection, Box 1, File 11, Item 14. Duncan Campbell Scott to Lorne Pierce, 16 October, 1924. For more on Aboriginal writers of the early twentieth century, like Charles A. Cooke and Edward Ahenakew, and their struggles to write back against popular (mis)conceptions of Indians, see: Brendan Frederick R. Edwards, A War of Wor(l)ds: Aboriginal Canadian writing during the "dark days" of the early twentieth century. (Doctoral dissertation, Department of History, University of Saskatchewan, 2008). back

36. James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans; a narrative of 1757 (Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, 1826). Cooper's classic novel has been republished innumerable times, translated into several languages, and has inspired countless theatre, television, film, and comic book renditions. In film alone there have been at least 17 productions, the most famous being that directed by Michael Mann in 1992, starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, and Russell Means. Martin Baker and Roger Sabin refer to The Last of the Mohicans as a "book that everyone knows but that few have read." Nonetheless, its inspirational and influencing qualities (right or wrong) apparently know no bounds. For more, see: Baker and Sabin, The Lasting of the Mohicans: history of an American myth (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995). back

37. George Harrison Orians, The Cult of the Vanishing American: a century view, 1834-1934 (Toledo: H.J. Chittenden, 1934). See also: Brian W. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White attitudes and U.S. Indian policy (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1982) 21-25. back

38. Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1855). Longfellow's poem initially received widespread success and praise, but after a decade it became a popular source of ridicule and popular satirical imitation – another sign of its widespread appeal and notoriety. back

39. Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Random House, 1979). back

40. A distinctly Canadian literature that worked to achieve this included works by missionaries such as John Maclean, John McDougall, and Egerton Ryerson Young. Their most influential works included: John Maclean, The Hero of the Saskatchewan: life among the Ojibway and Cree Indians in Canada (Barrie: Barrie Examiner Printing & Publishing House, 1891); Maclean, The Indians of Canada (Toronto: William Briggs, 1889); McDougall, Indian wigwams and northern campfires: a criticism (Toronto: William Briggs, 1895); Young, By Canoe and dog-train among the Cree and Salteaux Indians (Toronto: William Briggs, 1890); Young, Stories from Indian wigwams and northern camp-fires (Toronto: William Briggs, 1893). Daniel Francis discusses the influence of missionary writers in early Canada in The Imaginary Indian: the image of the Indian in Canadian culture (1992; Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1995) 44-60. back

42. See: Jacek Matwiejczyk, "Going Tribal / Pióropusze nad Wista" Kaleidoscope 82.8 (August 2005): 50-56; Joe MacDonald, John Paskievich, and Ches Yetman, If Only I Were an Indian. ([Montréal]: National Film Board of Canada, 1995). back

43. "Do vily sa nastahoval u'aj Indian." Atlas.sk (2006). 18 January, 2006, <http://dnes.atlas.sk>. Similarly, the popular Slovak ska-punk band, ska pra šupina, references Karl May's Winnetou in their song, "Barbie" (from their 2000 album "Zblíži a poteší," music and lyrics by ska pra šupina). back

44. Richard H. Cracroft, "Foreword." Karl May, Winnetou. Translated and abridged by David Koblick (1892-93; Pullman: Washington University Press, 1999) xvi-xvii. back

46. The best biographical work on Grey Owl is, to date: Donald B. Smith, From the Land of Shadows: the making of Grey Owl (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1990). back

47. W.H. New, A History of Canadian Literature. Second Edition (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003) 110. back

48. Smith, From the Land of Shadows, 17. back

49. See: Smith, From the Land of Shadows, 41. Longfellow included a 150 word Ojibwa vocabulary at the end of The Song of Hiawatha, using the writings of former American Indian Agent, Henry Schoolcraft. back

50. Ernest Thompson Seton, Two Little Savages: being the adventures of two boys who lived as Indians and what they learned (New York: Doubleday Page & Company, 1903) 1. back

51. "Grey Owl Lionized," The Daily Herald [Prince Albert, Saskatchewan] (August 14, 1936) 1. It is interesting and significant to note that it was at the Carlton Treaty No. 6 celebration that the Plains Cree confirmed their doubts about Grey Owl's authenticity. Although the Cree honoured Grey Owl as a brother, and showed him much attention, his behaviour and manner at the celebration gave them a clear indication that he did not have the "genre and ethos of an Indian." Euro-Canadians and non-Aboriginals, like Lord Tweedsmuir, were as yet still utterly convinced of Grey Owl's Indian background. For more, see Donald Smith's biography, From the Land of Shadows 160-161. back

52. Smith, From the Land of Shadows 155, 163-164. back

53. See: Lord Tweedsmuir to Lady Tweedsmuir, 22nd September, 1936; Lord Tweedsmuir to "Dearest Tim", 16th September, 1936; Lord Tweedsmuir to Alastair Buchan, 15th September, 1936; Lord Tweedsmuir to W. L. Mackenzie King, 29th September, 1936. All in: Queen's University Archives. John Buchan Papers (Collection 2110), Series 1 (Correspondence), Box 8, File 1. back

54. Robert Kroetsch, Gone Indian (1973; Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1999) 84. back